In the past month alone, nearly 10 million Americans have relied on some form of sleeping aid, seeking relief from the increasingly common issue of insomnia.1,2 While these drugs may seem like a quick fix for sleepless nights, their long-term consequences on health are not as well understood as their immediate effects. Z-drugs (nonbenzodiazepines) and benzodiazepines are two classes of medications commonly prescribed as sleeping pills, but their safety and effectiveness are subjects of increasing concern.

Understanding Z-Drugs and Benzodiazepines

While Z-drugs are chemically distinct from benzodiazepines, they work in much the same way.3 Both act on the central nervous system by targeting the same neurotransmitter receptors in the brain, primarily gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors, which inhibit brain cell activity.1,3 This mechanism, common to both classes of drugs, has led to their use as sedatives.3 However, this same mechanism is also responsible for their potential to cause physical dependence when taken regularly for more than a few weeks.3

Some of the most common Z-drugs include:

- Zopiclone (Brand names: Zimovane, Imovane)

- Zolpidem (Brand names: Ambien, Stilnoct)

- Zaleplon (Brand name: Sonata)

- Eszopiclone (Brand name: Lunesta)

Despite their chemical differences, these drugs can cause physical dependence and withdrawal symptoms, similar to those experienced with benzodiazepines.3 Studies have raised concerns that while Z-drugs may have more favorable pharmacokinetic profiles (how the body absorbs and processes the drug), their adverse effects—including neuropsychiatric issues and an increased risk of poisoning and death—could be similar to older hypnotics, such as diazepam (Valium) and temazepam (Restoril).4,5,6

Notably, it is not recommended to use Z-drugs as an alternative to benzodiazepines during withdrawal, as they may perpetuate or exacerbate the same risks.1,3

How Do Sleeping Pills Work?

The older sedative-hypnotic drugs, like diazepam, were initially designed to sedate the user, not necessarily to aid in the natural process of falling asleep.1 Sleeping pills, whether older or newer, share this sedative effect.1,3 Both classes of drugs target the same brain system as alcohol, affecting the brain’s receptors that inhibit neural activity, creating a calming effect.1,3 This process is part of the broader category of sedatives, which are commonly used to help people fall asleep or calm down.

However, these medications do not promote natural sleep. Instead of helping users reach the restorative sleep stages essential for health, they merely mask sleep problems, often with detrimental consequences.

Natural Sleep vs. Drug-Induced Sleep

The sleep induced by sleeping pills differs significantly from natural, restorative sleep. When comparing brainwave activity in natural deep sleep versus sleep induced by medications like zolpidem (Ambien) or eszopiclone (Lunesta), researchers have found that the electrical signature of drug-induced sleep is deficient. Specifically, it lacks the deep, slow-wave brain activity that is critical for the brain’s restorative functions, such as memory consolidation.7

In a study by researchers at the University of Pennsylvania, animals that underwent intense learning were given either a placebo or a dose of Ambien before sleep. The results were striking: natural sleep facilitated the strengthening of brain connections related to new memories, while Ambien-induced sleep resulted in a 50% weakening (unwiring) of those connections.8 This suggests that drug-induced sleep does not reinforce memories as effectively as natural sleep, potentially erasing the very learning it is meant to consolidate.

The Rebound Insomnia Dilemma

One of the most troublesome side effects of sleeping pills is rebound insomnia. This phenomenon occurs when individuals stop taking their medication after prolonged use, only to experience even worse insomnia than before they started the drug. This happens because the brain adjusts to the drug by altering its receptor balance, becoming less sensitive to its own natural sedative mechanisms.1

When the drug is suddenly removed, the brain’s new balance is disturbed, and sleep worsens. This is why many individuals, despite initially seeking relief from insomnia, often find themselves trapped in a cycle of physical dependence, where their sleep quality only deteriorates further with continued use.

Do Sleeping Pills Actually Work?

A meta-analysis of 65 studies involving nearly 4,500 participants examined the effectiveness of newer sedative sleeping pills. The findings were sobering: while participants felt they fell asleep faster and experienced fewer awakenings, objective measures of sleep quality—such as sleep recordings—showed no significant difference between those taking sleeping pills and those taking placebos.9 This suggests that the subjective experience of better sleep is not supported by actual improvements in sleep quality.

Even the latest sleeping pill, suvorexant (Belsomra), a dual orexin receptor antagonist (DORA), has been shown to offer minimal benefits, with improvements in sleep latency and duration measured in mere minutes.1,9 Such results underscore the pharmacological limitations of current sleep aids and their inability to replicate natural, restorative sleep.

Are Sleeping Pills Harmful?

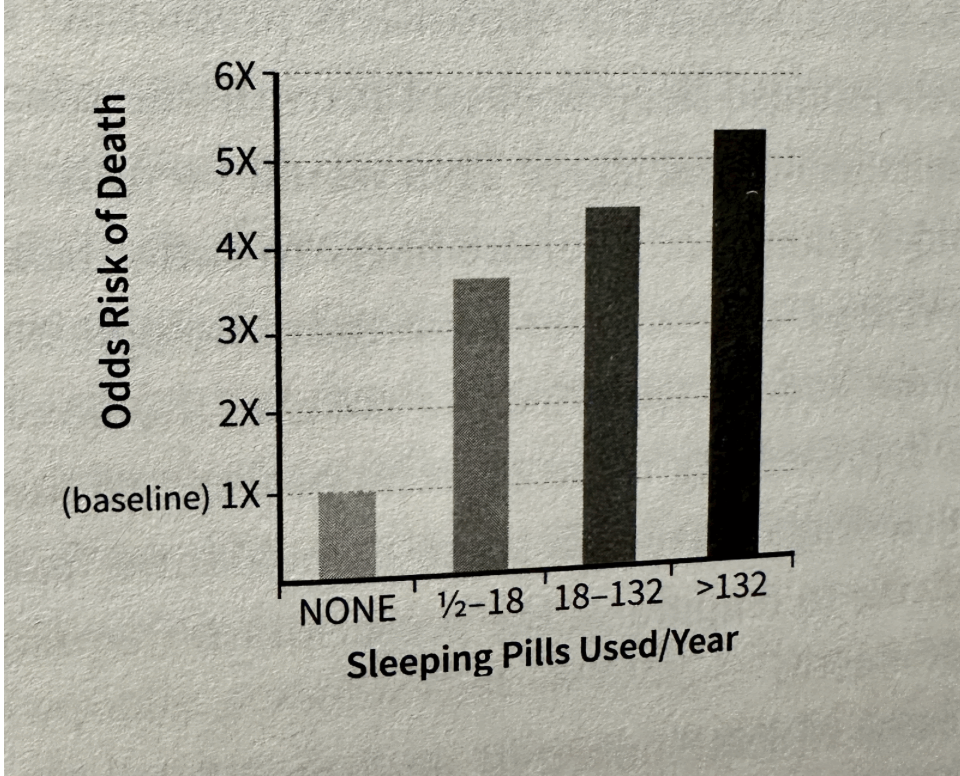

While the immediate effects of sleeping pills may seem beneficial, their long-term use can have serious consequences. Numerous studies have shown that individuals who use sleeping pills are at a higher risk of developing severe health problems, including death.11

In a landmark study by Dr. Daniel Kripke at the University of California, San Diego, individuals who used sleeping pills were found to be 4.6 times more likely to die within 2.5 years compared to those who did not use these medications.12 The risk of death increased with the frequency of use, and even occasional users were significantly more likely to die than non-users.12 In addition to the increased risk of death, the study also found a 30-40% higher likelihood of cancer in those who used sleeping pills.12

So, what accounts for these alarming statistics? One contributing factor could be the impact of sleeping pills on the immune system. Natural sleep is a powerful booster of immune function, while drug-induced sleep may not provide the same restorative benefits.1 This immune suppression could leave individuals more vulnerable to infections, especially the elderly, who are the heaviest users of sleeping pills.1

Moreover, sleeping pills have been linked to an increased risk of accidents, such as fatal car crashes, possibly due to the lingering grogginess or non-restorative sleep they induce.1 In addition, they have been associated with a higher risk of falls, heart disease, and stroke.1

Cancer Risk and Sleeping Pills

Perhaps the most unsettling finding of all is the potential link between sleeping pill use and cancer. Kripke’s study revealed that individuals taking sleeping pills were significantly more likely to develop cancer over a 2.5-year period than non-users.11 This risk was even higher for users of older medications like temazepam (Restoril), with those taking higher doses of zolpidem (Ambien) also exhibiting a 30% greater risk of developing cancer.11

Animal studies have also hinted at the carcinogenic potential of these drugs, with rats and mice showing increased cancer rates after prolonged exposure to common sleeping pills.1 While these findings don’t prove causation, they raise critical concerns about the long-term safety of these medications.

Z-Drugs: Physical Dependence and Withdrawal

Like benzodiazepines, Z-drugs can lead to physical dependence and withdrawal symptoms, and are therefore recommended for short-term use only (typically 2–4 weeks).3,14 Numerous anecdotal reports from the online withdrawal community describe Z-drug withdrawal as being of similar severity and duration to benzodiazepine withdrawal. Each Z-drug has an equivalent dose to diazepam and should be tapered gradually to reduce the intensity of withdrawal symptoms.3 However, tapering directly from a Z-drug can be difficult due to their short half-lives and limited availability in forms other than standard tablets.14 In some cases, individuals may have the Z-drug compounded into a liquid form for easier tapering.14 Alternatively, some may switch to an equivalent dose of diazepam for tapering, which offers the advantage of a longer half-life.3,14

Sleeping Pills and Pregnancy

A recent scientific review of Ambien from a team of leading world experts stated: “[the] use of zolpidem [Ambien] should be avoided during pregnancy. It is believed that infants born to mothers taking sedative hypnotic drugs such as zolpidem [Ambien] may be at risk for physical dependence and withdrawal symptoms during the postnatal period.”15

Conclusion: Are Sleeping Pills Worth the Risk?

The evidence surrounding the use of sleeping pills is clear: they may not provide the natural, restorative sleep your body needs, and their long-term use can be harmful to your health. The risks associated with sleeping pills—ranging from increased mortality and cancer risk to immune suppression and cognitive impairment—are significant and should not be underestimated.

Before reaching for a pill to address your sleep problems, it’s important to consider these risks and explore alternative treatments. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I), for example, has been shown to be an effective, long-term solution without the harmful side effects of sleeping pills.1 CBT-I builds on basic sleep hygiene principles. Some obvious methods include reducing caffeine and alcohol intake, removing screen technology from the bedroom, and maintaining a cool sleep environment. In addition, CBT-I may involve establishing a regular bedtime and wake-up time—even on weekends—going to bed only when sleepy and avoiding falling asleep on the couch in the early or mid-evening, and never lying awake in bed for extended periods. Patients are also encouraged to avoid daytime napping, learn to mentally decelerate before bed, and remove visible clock faces from view. Twelve more general sleep hygiene recommendations can be found on The National Institutes of Health website.16 Lastly, it’s important to recognize that sleep and physical exertion have a bidirectional relationship.1

Ultimately, while sleeping pills may offer short-term relief, they should not be seen as a solution for chronic sleep issues. By understanding the potential dangers and making informed choices, you can prioritize your health and well-being without relying on potentially harmful medications.

References

- Walker, M. P. (2017). Why we sleep: Unlocking the power of sleep and dreams (pp. 282–295). Scribner.

- American Academy of Sleep Medicine. CDC releases first estimate of prescription sleep aid use. AASM. Published August 29, 2013. Accessed May 13, 2025. https://aasm.org/cdc-releases-first-estimate-of-prescription-sleep-aid-use/

- Ashton, H. (2002). Benzodiazepines: How they work and how to withdraw (The Ashton Manual) (Version 3). University of Newcastle. Retrieved from https://www.benzo.org.uk/manual

- Gunja N. (2013). The clinical and forensic toxicology of Z-drugs. Journal of medical toxicology : official journal of the American College of Medical Toxicology, 9(2), 155–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13181-013-0292-0

- Geulayov, G., Ferrey, A., Casey, D., Wells, C., Fuller, A., Bankhead, C., Gunnell, D., Clements, C., Kapur, N., Ness, J., Waters, K., & Hawton, K. (2018). Relative toxicity of benzodiazepines and hypnotics commonly used for self-poisoning: An epidemiological study of fatal toxicity and case fatality. Journal of psychopharmacology (Oxford, England), 32(6), 654–662. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881118754734

- Koniuszewski, F., Vogel, F. D., Dajić, I., Seidel, T., Kunze, M., Willeit, M., & Ernst, M. (2023). Navigating the complex landscape of benzodiazepine- and Z-drug diversity: insights from comprehensive FDA adverse event reporting system analysis and beyond. Frontiers in psychiatry, 14, 1188101. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1188101

- Arbon, E. L., Knurowska, M., & Dijk, D. J. (2015). Randomised clinical trial of the effects of prolonged-release melatonin, temazepam and zolpidem on slow-wave activity during sleep in healthy people. Journal of psychopharmacology (Oxford, England), 29(7), 764–776. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881115581963

- Seibt, J., Richard, C. J., Sigl-Glöckner, J., Takahashi, N., Kaplan, D. I., Doron, G., de Limoges, D., Bocklisch, C., & Larkum, M. E. (2014). Cortical dendritic activity correlates with sleep-dependent memory consolidation. Nature Neuroscience, 20(9), 1277–1283. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.4109

- Huedo-Medina, T. B., Kirsch, I., Middlemass, J., Klonizakis, M., & Siriwardena, A. N. (2012). Effectiveness of non-benzodiazepine hypnotics in treatment of adult insomnia: Meta-analysis of data submitted to the Food and Drug Administration. BMJ, 345, e8343. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e8343

- Citrome, L. (2014). Suvorexant for insomnia: A systematic review of the efficacy and safety profile for this newly approved hypnotic—What is the number needed to treat, number needed to harm and likelihood to be helped or harmed? International Journal of Clinical Practice, 68(12), 1429–1441. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.12568

- Kripke, D. F., et al. (2012). Hypnotics’ association with mortality or cancer: A matched cohort study. BMJ Open, 2(1), e000850. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000850

- Source: Dr. Daniel F. Kripke, “The Dark Side of Sleeping Pills: Mortality and Cancer Risks, Which Pills to Avoid & Better Alternatives.” March 2013, accessed at http://www.darksideofsleepingpills.com

- Glass, J., Lanctôt, K. L., Herrmann, N., Sproule, B. A., & Busto, U. E. (2005). Sedative hypnotics in older people with insomnia: Meta-analysis of risks and benefits. BMJ, 331(7526), 1169. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.38623.768588.47

- Horowitz, M., & Taylor, D. (2022). The Maudsley prescribing guidelines in psychiatry (14th ed.). Wiley-Blackwell.

- MacFarlane, J., Morin, C. M., & Montplaisir, J. (2014). Hypnotics in insomnia: the experience of zolpidem. Clinical therapeutics, 36(11), 1676–1701. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2014.09.017

- “Tips for Getting a Good Night’s Sleep,” NIH Medline Plus, Accessed at https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/magazine/issues/summer12/articles/summer12pg20.html (or just search the Internet for “12 tips for better sleep, NIH”).