Now is the time to speak up. This is a worldwide call to action! These draft guidelines, if left uncorrected, will harm the very people they are intended to help. Your feedback can make a difference! Please share with your networks, online and offline!

The University of Western Australia has released draft Clinical Practice Guidelines for Deprescribing in Older People, covering benzodiazepines, sedatives and hypnotics, as well as other medications. While deprescribing guidance is important, these drafts contain serious problems that will harm many older adults.

The benzodiazepine and hypnotics and sedatives sections recommend dangerous tapering practices: reducing doses by 25–50% every 1–4 weeks, then stopping abruptly at half the lowest manufacturer dose. This ignores best practices and risks injury to vulnerable patients. Modern evidence supports slower, hyperbolic tapering tailored to each unique person.

We support their referencing the Maudsley Deprescribing Guidelines, which recommend numerous safer tapering strategies, but this does not offset the harm from the draft’s aggressive approach.

The draft also advises deprescribing for older adults who are already physically dependent, claiming risks usually outweigh benefits except in special cases like alcohol withdrawal or palliative care. This blanket approach is harmful. Any taper can cause lasting neurological injury and must only be done with informed consent and careful risk-benefit evaluation, also taking into consideration the patient’s wishes.

Major Concerns with the Draft Guideline

- The recommended taper rates are dangerous at 25% to 50% every one to four weeks.

- The guideline fails to acknowledge physical dependence, benzodiazepine-induced neurological dysfunction (BIND), and protracted withdrawal that can cause lasting disability and increase suicide risk.

- It puts older adults at risk by encouraging well-meaning but under-informed providers to force discontinuation without consent.

- It lacks a nuanced discussion of the risks and benefits of continued use versus tapering for long-term patients.

- It ignores patient autonomy and the documented harms from forced discontinuation without consent.

Links to Guidance and Survey

Feedback Survey

Hypnotics and sedatives

Benzodiazepine anxiolytics

Entire Draft Guidelines

If You Only Have 5 Minutes to Help

Fill out the survey (click here) by May 30 and comment:

This guideline misses both when and how to deprescribe and ignores the risks involved. The taper rates in the Hypnotics and Sedatives and Benzodiazepine Anxiolytics sections are dangerously outdated. This guideline promotes oversized, abrupt dose reductions that contradict current best practices, which call for tapering by 5 to 10 percent of the current dose, or less, every 4 weeks. The Maudsley Deprescribing Guidelines gets this right and should be adopted for the Benzodiazepine and Hypnotic and Sedatives sections (as well as the sections on Antidepressants and Antipsychotics). Forced deprescribing in older adults can be deadly. These recommendations overlook long-term harm and risk injuring the very population they aim to help.

Public Consultation Survey — What You Need to Know

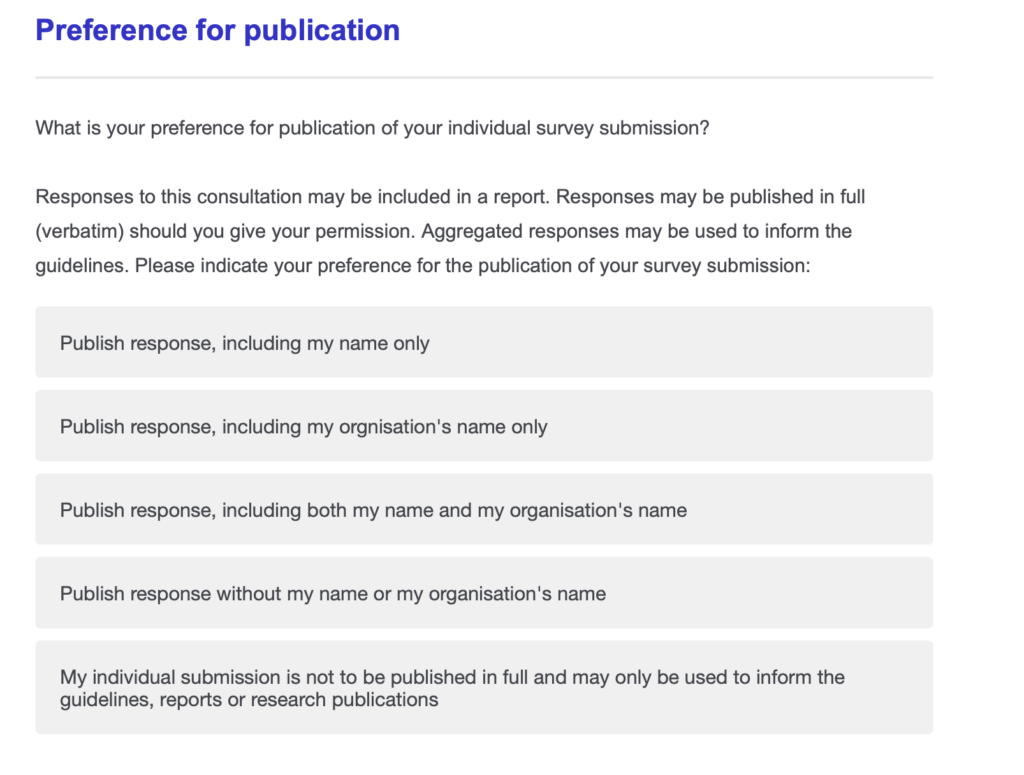

- Name and Email Required: The survey asks for your name and email, but you can use your real name, a pseudonym, or stay anonymous. You can choose how your identity is handled at the very end of the survey. See the photo above for the options.

- Open to Everyone: The survey is open internationally. When asked for your postal or ZIP code, use your local one if you’re comfortable sharing it.

- Draft and Survey Information: The drafts are short and easy to read, but the survey lacks

- About the Survey: The drafts are short and easy to read, but the survey lacks specific questions to support a thorough critique. It seems more focused on whether the guidance is useful rather than identifying serious flaws.

- Where to comment: To give meaningful feedback, fit your concerns into any open-ended questions about the value or application of the guidance.

- No Word Limit: There does not appear to be a limit on comment length, so be as thorough as needed.

- Question Paths Vary: Questions may differ depending on whether you identify as a patient, prescriber, caregiver, etc.

- Be Specific: Clearly identify which drugs or sections you’re addressing. Our feedback applies to both Hypnotics and Sedatives and Benzodiazepine Anxiolytics, as the draft covers multiple drug classes.

- Use Our Materials: You are welcome to incorporate our points and citations from the Key Concerns, Deprescribing Guidelines in Conflict, or Research on Withdrawal Severity and Suicidality sections below in your responses.

- Deadline: Submit your comments by May 31 (Western Australia time). For most international time zones, that means submit by May 30.

Benzodiazepine Deprescribing Guidelines In Conflict with the UWA Guideline

The UWA draft guideline conflicts with multiple established best practices for safe benzodiazepine deprescribing:

- The Maudsley Deprescribing Guidelines recommend 5–10% dose reductions every 2–4 weeks for patients prescribed benzodiazepines long-term, reserving more rapid tapers for short-term users without significant risk factors for withdrawal effects. For longer-term patients with greater risk factors it suggests tapers that are even slower than 5% dose reductions per month. These reductions are based on the current dose, so reductions become smaller as the dose lowers. While this guideline mentions Maudsley, it should go further. Maudsley represents the current best practice and should be directly adopted to reduce harm.

- Kaiser Permanente’s Benzodiazepine and Z-Drug Safety Guideline defines a slow taper as 10% every 2–4 weeks and rapid as 25% every week. This UWA guideline recommends tapering rates that are faster than even the “rapid” protocols in other established guidance.

- The Joint Clinical Practice Guideline on Benzodiazepine Tapering, published in 2025 by numerous American medical and professional societies recommends that the initial pace of the benzodiazepine taper should generally include dose reductions of 5% to 10% every 2–4 weeks. The taper should typically not exceed 25% every 2 weeks. This guideline exceeds that.

- Scotland’s Polypharmacy Guide for Realistic Prescribing recommends that withdrawal should be gradual (e.g. 5–10% reduction every 1–2 weeks, or an eighth of the original dose fortnightly, with a slower reduction at lower doses), and titrated according to the severity of withdrawal symptoms.

- Both Scotland’s Polypharmacy Guide for Realistic Prescribing and the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence state that prescribers should not pressure the person to stop if they are not motivated to do so. This guideline instead issues a blanket recommendation to deprescribe in older adults, contradicting this recommendation.

- The Ashton Manual states that the decision to withdraw is the patient’s decision and it should not be forced by the doctor. This guideline contradicts the recommendation.

Benzodiazepine Withdrawal Severity and Suicidality Research

The UWA guideline completely ignores the long-term risks of deprescribing, including patient harm and death. The following research highlights important complications of benzodiazepine withdrawal that have been overlooked:

- Maust et al. (2023) found increased mortality linked to benzodiazepine deprescribing. The authors stated: “These results suggest benzodiazepine discontinuation among patients prescribed for stable long-term treatment may be associated with unanticipated harms, and that efforts to promote discontinuation should carefully consider the potential risks of discontinuation relative to continuation.”

- Ritvo et al. (2023) reported that some individuals continued to experience symptoms a year or more after discontinuing benzodiazepines.

- Finlayson et al. (2022) found that among people who had discontinued benzodiazepines, 54.4% reported suicidal thoughts or attempts, and 46.8% reported losing employment as a result of their use or withdrawal.

- FDA (2020) determined that withdrawal symptoms can last from weeks to years, with a median duration of 9.5 months based on their case series review.

- Dodds (2017) concluded that benzodiazepines may increase the overall risk of suicide attempts and completions. Suggested mechanisms include rebound symptoms, impulsivity, aggression, and toxicity in overdose.

I’m in the last stage of COPD, in other words, dying of slow suffocation. I have been put into Diazepam withdrawal against my will (what possible point could there be after 50 years, and at the end of my life?)

So far, I’ve been suffering more from the withdrawal than from the COPD for 29 months. It caused me to become housebound and virtually immobilised many months before the COPD did. I consider suicide every day and only wish I had done it the moment the doctors told me their intentions. I have asked what the point is for a dying person and nobody will answer.

I was prescribed Xanax for 25 years & eventually got a DUI for driving under the influence of it. I was thrown in jail for 3 nights & started to withdraw, went into a seizure, was taken to ER & nearly died. I went to rehab from there & am off of it. The prescribing doctor got his license permanently removed & I have severe long-standing issues from Xanax. I suffer from extreme weakness, muscle aches, anger, irritability, impatience, severe frustration, tooth decay, back problems, chronic kidney disease & liver damage. I am considering suing the physician.

Re: Deprescribing Guidelines For Older People

I take a benzodiazepine (clonazepam 2mg) as maintenance due to a month in Catatonia that caused severe malnourishment and dehydration. My Catatonia was caused by an extreme fear response, exacerbated by a severe brain injury.

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/02698811231158232

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8900590/

https://psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.neuropsych.17060123?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%20%200pubmed

To my horror, I found that very few doctors worldwide know what Catatonia is, how to diagnose and how to treat.

In older adults, rapid discontinuation of benzodiazepines cause catatonia, as well as rapid discontinuation of anti-psychotics. Drug withdrawal Catatonia is common, but under diagnosed due to a lack of medical training and patients are left to linger for years in psychiatric wards or intensive care units.

I now work with families of patients with Catatonia to provide them with resources. Which is ridiculous because physicians should be identifying Catatonia, especially drug withdrawal Catatonia, and resolving it as well as recognizing it as a potentially deadly consequence when de-prescribing/tapering benzodiazepines.

Yes, there are many negative consequences to benzodiazepine withdrawal, but nowhere am I seeing Catatonia as the most dangerous consequence.

Could your organization address this issue? The guidelines are dangerously incomplete because they ALL omit Catatonia as a dire consequence of too rapid de-prescribing/tapering schedules. Physicians, patients and families need to be educated and informed!

Thank you!

Helen, YES, I was catatonic when I abruptly quit Xanax after using it for 25 years. I was hospitalized & couldn’t even speak to people. Thank you for this very important reminder of an effect of benzo withdrawal.